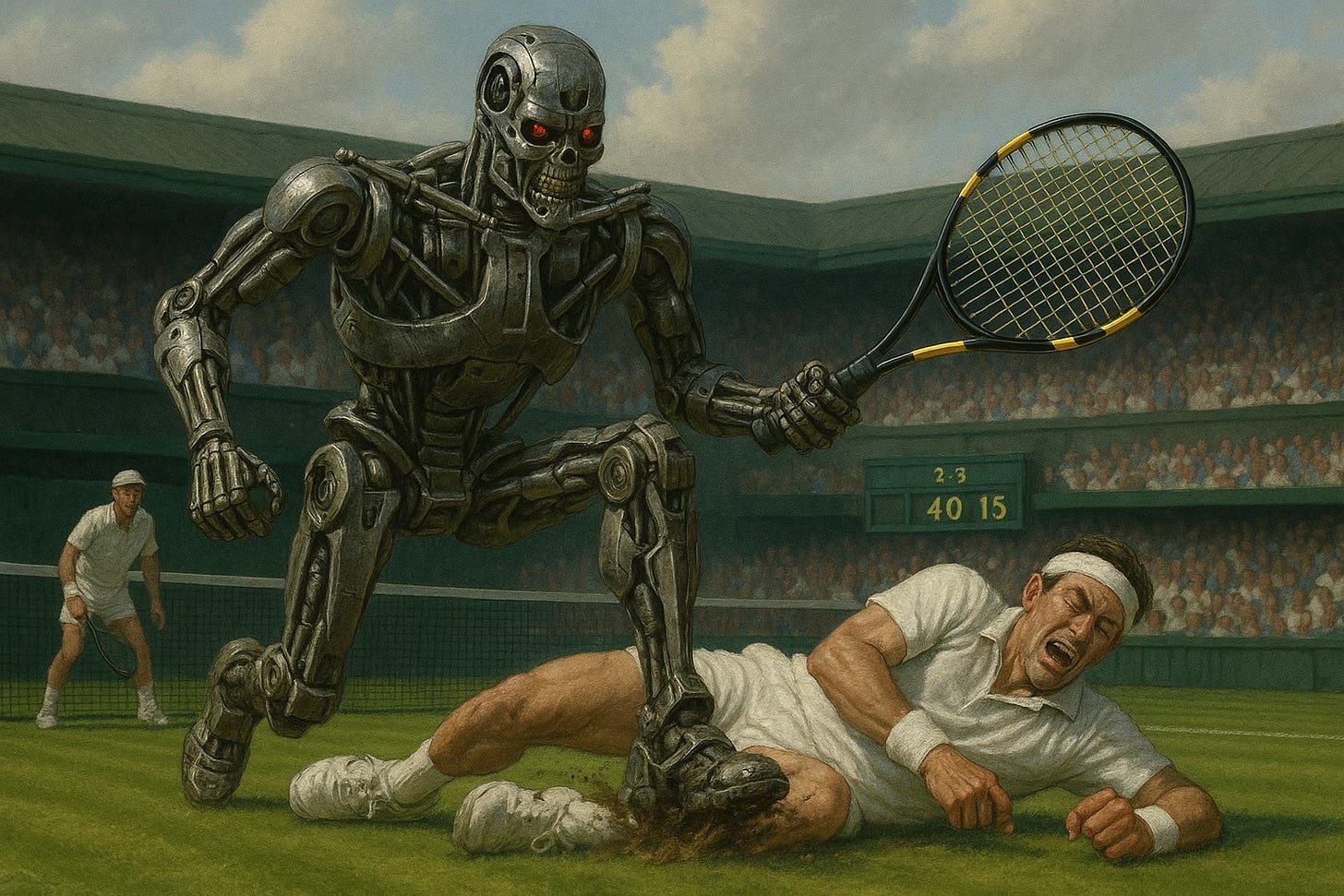

The future of tennis flashed before my eyes. An apocalyptic wasteland dominated by baselining cyborgs on courts paved with the bodies of serve and volleyers like me.

It’s not like I wasn’t warned.

Baseline rallies were getting longer, topspin heavier.

Tennis was changing.

The fans, the newspapers, even tennis’s governing body, the ATP, weren’t happy with the short quick points and big serves that dominated 90’s tennis. The message was clear: Tennis needed to head to the baseline.

To do that, it needed to slow down. Fast.

As a kid, I didn’t just pick serve-and-volley tennis, the fastest of the game styles, because it worked—I picked it because it mattered.

It was a pure art form. An artistic kid, I actually chose to go to art camp. Loved it — I wasn’t one to chase frogs, but ask me to draw one, and bam, you got a frog.

I saw tennis as a perfect storm of creativity, athleticism, and solitude. The court my canvas, and serve and volley my minimalist art, of quick points, extreme angles, and explosive overheads.

Serve and volleyers like Grant Connell, Pete Sampras, John McEnroe, these were the tennis artists I aspired to be like.

Early on, it worked. My net rushing caught fire in the under 14s. I was running through tournaments like a chainsaw through a piñata.

I wasn’t just winning—I was stylishly winning.

If I’m being totally honest, it always felt like my canvas was pushing back.

Every year new versions of racquets crafted out of newly discovered futuristic materials made it a little easier for my baseline opponents to handle my serve and volley attack. Hyper Carbon, Titanium, Liquid Metal.. was this tennis or a Space Mission?

Passing shots got faster, topspin made balls heavier. Topspin lobs that sailed out before, were now dipping in.

Strings promised more POP!

Fitness got ferocious. Balls fluffed. Courts slowed. Everything became about the grind!

When Wimbledon—the cathedral of serve-and-volley tennis—made the unthinkable decision to replaced its traditional grass with 100% perennial rye in a blatant attempt to slow down serves, it wasn’t just about making the matches more spectator friendly—it was about identity: if the top stage of the game was prepared to kill serve and volleyers, surely the rest of the world would follow suit.

In the early 2000s, for the first time, the baselines of the All England Club turned brown and trampled, while the net area stayed pristine.

Still, as a nineteen year old net rusher, I convinced myself I’d be okay.

I landed an ATP point serving and volleying on the fast courts at Jarry Park in Montreal.

I landed a scholarship to Ole Miss.

I told myself the tennis pendulum would swing back once it saw that slowing the sport was killing the very art form that made it special. Baseline bashing is boring! Surely the world will agree.

Even if the sport did become a baseline slog on quicksand, I’d find fast courts somewhere. Indoor tournaments in cold Canadian towns, Scandinavian carpet leagues; I could outrun the future.

But then a moment hit, and I knew I was done.

November 2, 2000 – Athens, Georgia

Three months into my freshman year at Ole Miss, I was 2–6 in singles and understood why my coach told me to avoid the South.

The slow, humid conditions were a death sentence for serve-and-volleyers. The courts sandpaper. The humidity clung to every step, the players all European and South American grinders, built for fluffy baseline tennis.

At the Southeast Regionals in Athens, Georgia I drew a fellow freshman. My opponent, playing for Tulane—a stocky, unbothered Scandinavian—pulled a racquet out of his bag I’d never seen.

The frame said “Babolat.” At the time, I thought Babolat just made strings. I had no idea they had quietly acquired the old Pro Kennex molds and started building the future—one graphite missile at a time.

Usually you can get a feel for the game you’re about to face based on your opponent’s racquet. My racquet the Wilson Classic - elegant, thin-beamed— was a dead giveaway that I was a player who played with feel; a serve and volleyer’s scalpel.

Based on the shape and round face of this Babolat, it was a power racquet that one of the ladies on my mom’s league team would use.

I served first, and went with serve and volley 101: A heavy slice serve out wide to his forehand, he caught it late, poked a weak return down the line I stuck a backhand volley deep to the open court: 15-0. So far so good.

On the next point, he made an adjustment and stood way behind the baseline, almost against the wall. A rookie move. In theory, a good idea – more space equals more time – but in reality it (usually) didn’t work. Giving himself more time also gave me more time to get close to the net, cover the angles, and take my first volley above the net.

I flicked a kicker to his backhand pulling him outside the doubles alley. As I ran in I watched my serve kick, peak, and then start to dip again.

As I was crossing the service line he managed to stretch his left leg behind the ball and... BOOM!... snap an openstance cross court two handed backhand that moved so fast all I could do was watch it shoot past me.

As the sound echoed through Athens’ tennis stadium like the crack of the first rifle on the prairies, I stood there in shock.

I’d never seen anything like that. It wasn’t possible. Players had only ever floated a return from that position, or tried that shot and sent over a weak return.

It had to be the racquet, right? I looked down at my skinny Classic and it looked up at me trembling in fear: You can’t beat this thing! Surrender now!

The arm cannon kept delivering, passing shot after passing shot, and, like the violinists on the Titanic playing while sinking to their death, I continued my passion to a 6-3 7-6 loss.

Walking off the court, I felt like I was coming out of a doctor’s office after being told my tennis game didn’t have much time; three maybe six years tops.

It didn’t matter how slow or fast the courts were going to get, racquet technology was going to make serve and volleying — the game style I’d dedicated my life to — obsolete.

What’s worse is I had no contingency plan.

The reason I had fallen in love with tennis in the first place—the artistry, the surprise, the creativity—had been replaced by a new logic I hadn’t prepared for.

My baseline game existed for decoration - plan B of retreat not something I could win with.

I built my entire tennis identity around a style that the sport had quietly phased out.

There is a lesson in this! It’s not all about feeling sorry for me, but thank you if you do. I’m a sucker for woe is me.

It is tempting to believe that staying true to your roots is noble. In tennis, as in life, stubbornness disguised as integrity eventually becomes self-sabotage.

You don’t have to constantly change everything, but if you want to survive, and thrive—you have to adapt. The future does not wait for aesthetic preferences. The game will keep moving, and your job is to move with it.

Here are some ways to prepare for the future - not just of tennis, but other pursuits.

HOW TO TRAIN FOR THE FUTURE

1. Pay attention to outliers. Medvedev standing near the back fence, Alcaraz mixing 100mph forehands with feathery drop shots. These aren’t one-offs. These are prototypes, and teasers for where the sport is headed. What starts as strange strategy becomes standard.

2. Your plan B should still be a winning strategy. Your Plan B has to feel like a Plan A—not something you fall back on out of fear, but something you use out of tactical surprise. If you’ve got a big serve, pair it with a killer kick. If your forehand is nuclear, develop a dropper you can hit with the same motion. Being dimensional means your opponent never knows what’s coming next, and you always have another way to win.

3. Always Be Physical. Tennis is becoming more physical every year. If you’re in doubt of how to win points, or what you should focus on, remember you can never go wrong getting fitter. Movement, economy and endurance aren’t add-ons—they’re essentials.

4. Slice. Okay this one is just tennis. The slice backhand, is the cockroach of tennis—it’s survived technical advancements, surface changes — everything. The slice builds your IQ while teaching you how to manipulate time; you can speed up, slow down, converse energy. Master the slice backhand. Weaponize it.

5. Embrace technology. Romanticizing old gear won’t save you. Racquets, strings, shoes, data—all of it is here to help you evolve. Be an early adopter, not a nostalgic casualty.

And as a writer? I try to stay so far ahead of the curve I’m practically out of style.

Want more stories like this, plus gear reviews, strategy lessons, and brutally honest tennis truths? Subscribe to my Substack:

➡️ Tennis Coach Conor Casey on Substack

Let’s get better together. Before it’s too late.

Become an Annual subscriber and get a free hat !

In my mind and on my court /

We can't rewind we've gone too far

Wimbledon killed the serve and volleyer /

Wimbledon killed the serve and volleyer

(Sung to the tune of The Buggles classic "Video Killed the Radio Star," of course)

On the flip side, for those with non-confrontational personalities on the court (me!), the baseline game is what drew me in. But I am still trying to learn! I spent two hours with a pro on Sunday, and we worked on the approach + volley over and over again. Will this turn me into Coach Conor? Of course not. But finishing points at the net is a skill every tennis player needs...especially as that tennis player gets older...!

Such an enjoyable read! Thanks very much for the sharing of the past, and the thoughtful view of the present/future.